Feb 20 • Sean Overin

GLP-1s, Osteoarthritis, and the Ecosystem of Cartilage

Empty space, drag to resize

I’ve been paying closer attention to the research around GLP-1 medications over the past year.

Like many clinicians, I initially thought about these drugs mostly in terms of weight loss and metabolic disease. But something else has been catching my attention, and others, in the literature and in the clinic.

Some patients with osteoarthritis are reporting changes in stiffness, flare-ups, and activity tolerance before any meaningful weight loss has been achieved.

Of course this got me curious.

And it sent me down another rabbit hole of research suggesting something important:

GLP-1 medications may be influencing the biological environment that cartilage cells live in, not just the load placed on the joint.

Like many clinicians, I initially thought about these drugs mostly in terms of weight loss and metabolic disease. But something else has been catching my attention, and others, in the literature and in the clinic.

Some patients with osteoarthritis are reporting changes in stiffness, flare-ups, and activity tolerance before any meaningful weight loss has been achieved.

Of course this got me curious.

And it sent me down another rabbit hole of research suggesting something important:

GLP-1 medications may be influencing the biological environment that cartilage cells live in, not just the load placed on the joint.

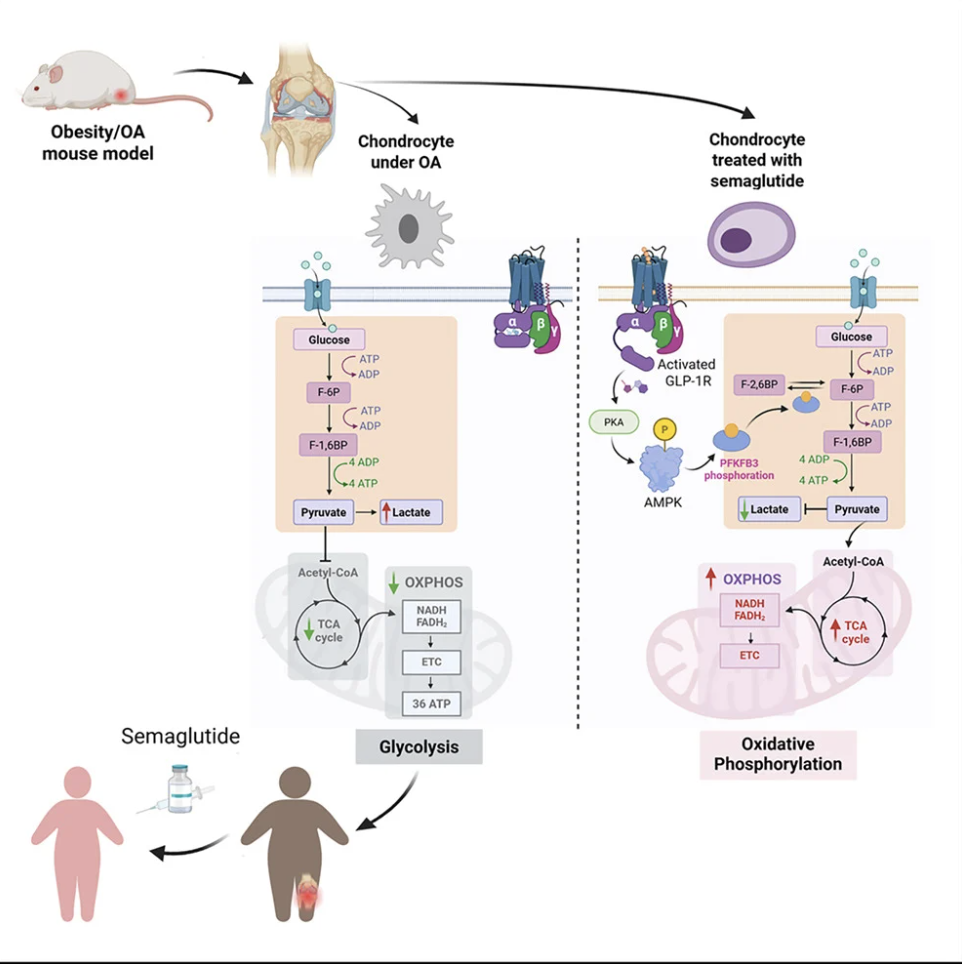

This diagram from Qin et al. 2026 shows that in osteoarthritis, cartilage cells (chondrocytes) tend to run in a stressed, inefficient “low-gear” mode, but when semaglutide is introduced (in a mouse model), those cells shift into a healthier, more efficient energy state.

This suggests the drug may help change the environment the cartilage cells live in, similar to moving cells from a polluted city to fresh mountain air.

A patient with severe symptomatic knee osteoarthritis I’ve been working with recently started a GLP-1 medication.

Within a few weeks of pain education, exercise, and the GLP-1 onboard, they were describing something much different, and earlier than I would normally expect: less morning stiffness, fewer flare-ups after longer walks, and a sense that their knee felt less cranky.

Side note: I say earlier because research shows that many people with symptomatic osteoarthritis follow a delayed-response trajectory, where meaningful improvements don’t appear until the 8–12 week mark.

Now back to the story...

I have seen this quick change a few times now so perhaps this isn't a coincidence...? Happy to be wrong here.

But a recent study in Cell Metabolism suggests a possible explanation. In a mouse model of osteoarthritis, semaglutide appeared to slow disease progression and improve cartilage health through mechanisms that were partly independent of weight loss.

Researchers observed quick changes in inflammatory signaling and cellular metabolism within cartilage tissue, suggesting that chondrocytes may function differently when the systemic metabolic environment changes.

It’s important to be cautious here. Animal models are valuable because they allow researchers to study cartilage biology and cellular pathways in ways that aren’t possible in humans.

Clearly, mouse joints and human osteoarthritis are not the same, and findings like these are best understood as early mechanistic evidence rather than clinical proof.

However, when mechanistic research begins to align with what clinicians are observing in practice, it’s usually a signal worth paying attention to.

A Shift in How We Think About Osteoarthritis

For a long time, osteoarthritis has been described as a wear-and-tear condition. That language is simple. It’s efficient. It helps people make sense of things. But it’s also incomplete. For most of you reading this, that’s not new.

Where many clinicians are landing these days in osteoarthritis care is this: helping patients understand that hurt does not equal harm, that pacing matters, and that exercises can be progressed over time. We’re building capacity, not protecting joints from inevitable decline.

For some individuals, weight loss may also play a role. There is a reasonable body of literature suggesting that even a 5% reduction in body weight correlates with meaningful changes in pain and function in people with OA. But like most research, it’s not perfectly consistent. And we all know how hard it is, practically, psychologically, metabolically, to lose weight and keep it off.

So yes, weight can be part of the story. But it’s not the whole story.

What makes the emerging GLP-1 research interesting isn’t that inflammation or metabolism matter. We’ve known or at least suspected that for years. What’s interesting is that we’re seeing changes in symptoms and function that are not fully explained by our current paradigms of exercise, building strength and flexibility, achieving weight loss, and as needed, reducing joint loading.

So what’s the new signal?

That systemic physiology should be closer to the forefront of our clinical reasoning.

GLP-1 medications may be another tool to help some people with OA. They still need exercise. They still need thoughtful load management. But can we create a better internal ecosystem, one that cartilage, pain systems, and joint irritability respond to?

And when stiffness settles sooner than expected…when activity tolerance improves faster than loading changes would predict…when irritability drops...

That’s interesting to me.

Osteoarthritis requires us to hold at least three lenses at once:

- Mechanical.

- Inflammatory.

- Metabolic.

Exercise and movement remain foundational. Weight loss can help many people. But emerging research suggests that some improvements may reflect shifts in systemic inflammation and metabolic health — not just changes in load or body mass.

As the evidence evolves, our practice should evolve with it.

- Therapeutic alliance still matters.

- Pain education still matters.

- Behaviour change still matters.

- Progressive loading still matters.

But the broader physiology of the person may deserve a more central place in our clinical reasoning. How would we address this? Yes, lifestyle health stuff, but this is hard to do. So ask your patient to check-in with primary care provider and see if this is an appropriate for the plan of care.

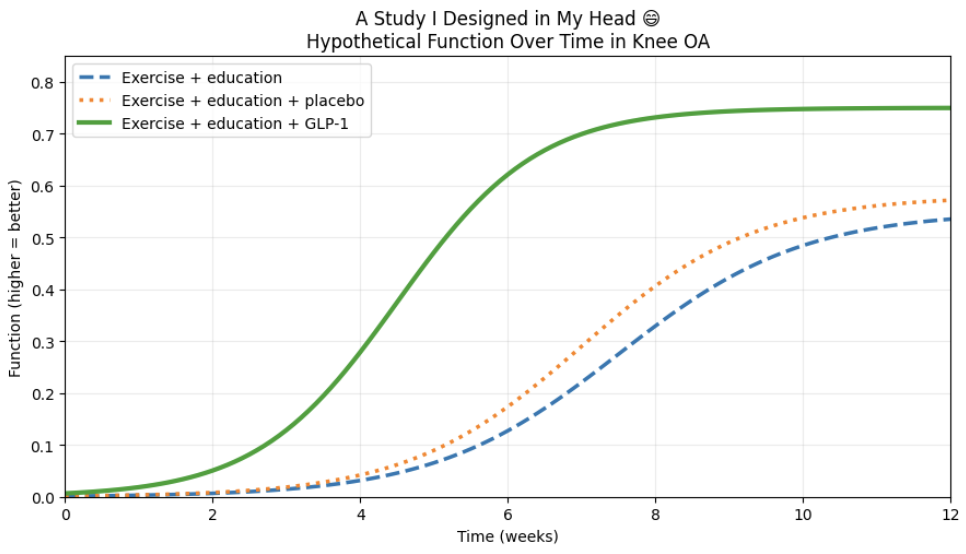

Who wants to fund my study ;)

Three groups start at the same place. Everyone gets education and exercise. Eventually, all three curves rise.

But one curve rises earlier. And maybe a bit faster.

Is it biology?

Is it behavior?

Is it expectation?

Is it some combination of all three?

A simple three-arm trial: education and exercise alone, the same program plus placebo, and the same program plus a GLP-1, could help clarify things.

Nanaimo, BC: April 12, 2026

Whitehorse, Yukon:

October 24 & 25, 2026...two full days of live needling reps.

Refine your symptom modification skills!

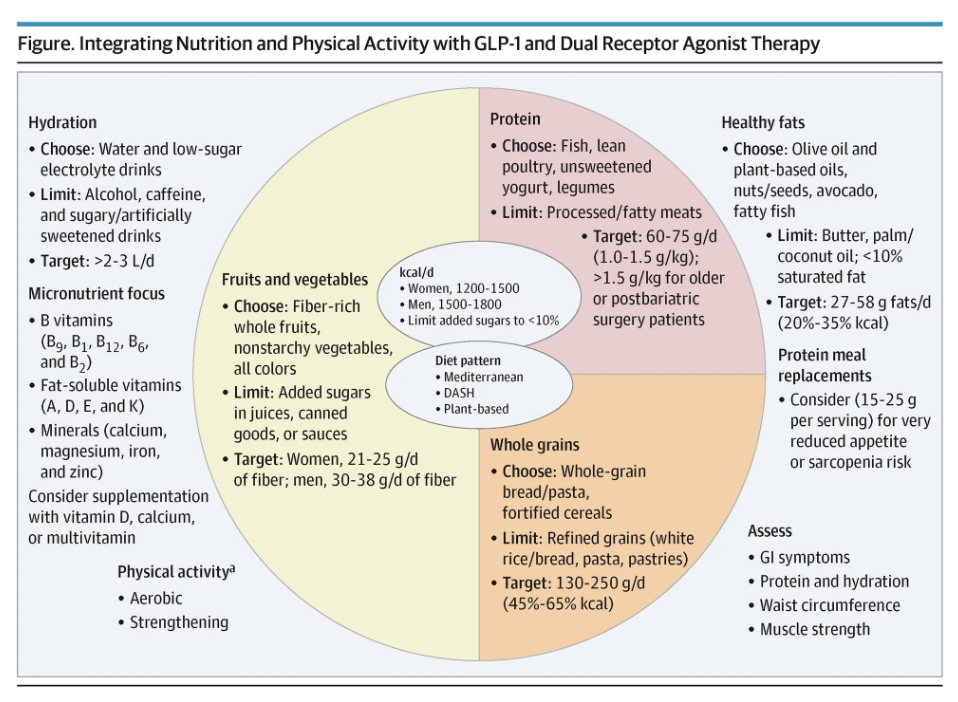

If you’re working with patients who are taking GLP-1 medications, there are two habits that deserve early attention.

Exercise for Osteoarthritis

Best exercise is the one that gets done. Most current evidence supports:

- 3-5 sessions per week

- Working major muscle groups

- Exercise that targets specific impairments (i.e. quadriceps, glutes, etc)

- Progressive loading where possible

Protein intake

A reasonable evidence-informed target for preserving muscle during weight loss is:

- 1.2–1.6 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day

Many patients on GLP-1 medications unintentionally under-eat protein because appetite is reduced. This is one of the most common gaps I see in practice.

Better metabolic health does not automatically mean stronger tissues.

Muscle and connective tissue still need stimulus + building blocks.

When patients are trying to increase protein intake, it doesn’t need to be complicated.

Encourage them to include a protein source at each meal:

- Eggs, Greek yogurt, cottage cheese, milk, chicken, turkey, lean beef, pork, fish like salmon or tuna, or seafood.

- For those who prefer plant-based choices, lentils, chickpeas, beans, tofu, tempeh, and edamame are good options, and variety across the day is usually sufficient.

- Convenient choices like protein shakes, protein bars, high-protein yogurt, or pre-cooked chicken or tuna packets can help, especially when appetite is low or schedules are busy.

"GLP-1 receptor agonists should be prescribed alongside structured lifestyle interventions—specifically resistance training at least 3 times weekly, 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise weekly, and nutrient-dense dietary counseling—to preserve muscle and bone mass, optimize weight loss, and improve cardiometabolic outcomes."

"Protein intake alone is insufficient without structured resistance training, and combination therapy produces superior metabolic benefits compared to pharmacotherapy alone, including better preservation of lean mass, improved cardiorespiratory fitness, and prevention of GLP-1-associated increases in resting heart rate."

I wrote earlier about this balance in a piece called

The central idea still holds:

GLP-1 medications can improve metabolic markers dramatically, but without strength training and adequate nutrition, people may lose meaningful lean mass.

Which matters for:

- Joint health

- Falls risk

- Long-term function

- Aging well

Researchers are actively working on next-generation therapies designed to target fat mass while preserving lean mass, reflecting growing recognition that body composition, not just weight, matters for long-term health and function: read more

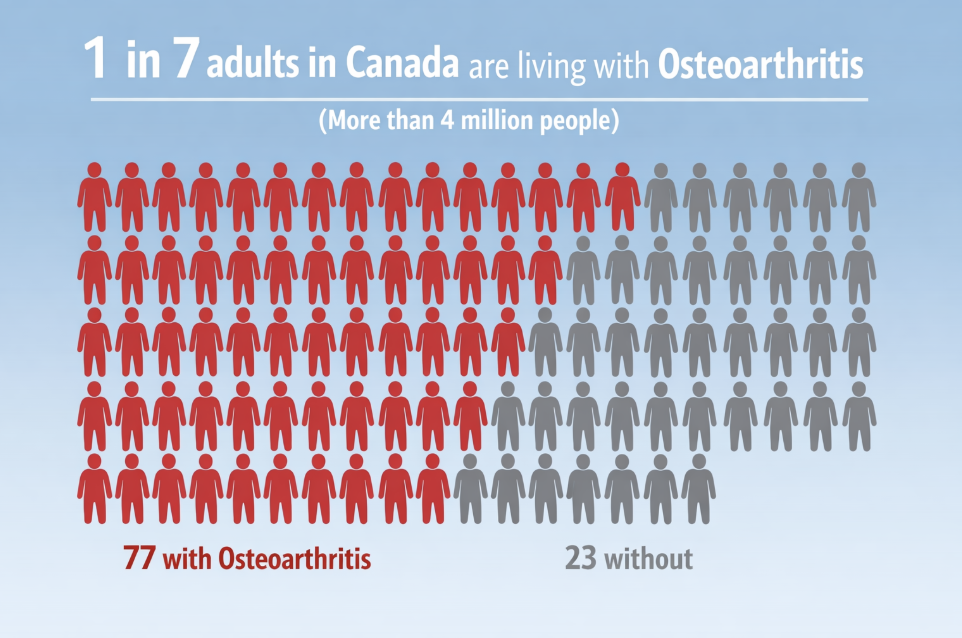

In Canada, an estimated 1 in 7 adults (more than 4 million people) are living with osteoarthritis, and that number is expected to rise significantly over the next decade as the population ages and rates of metabolic disease increase. We are not talking about a niche condition. We’re talking about something that touches nearly every family.

The future of OA care won’t just be about how people move. It needs to consider internal physiology supports that can be provided at scale for the right patient at the right time.

And let's remember:

Cartilage lives in a joint.

Joints live in a body.

And bodies live in lives, shaped by sleep, stress, movement, social context, food, and the rhythms of everyday living.

It’s all connected, whether we want to acknowledge it or not.

Stay nerdy,

Sean Overin, PT

Subscribe to our newsletter

Every Friday we cover must read studies, how they fit in practice, give it real world context, provide top resources and one sticky idea.

Thank you!

You have successfully joined our Friday 5 Newsletter subscriber list.