Empty space, drag to resize

This week I had the pleasure of hearing

Dr. Jackie Whittaker pull back the curtain on something much bigger than post-traumatic knee osteoarthritis.

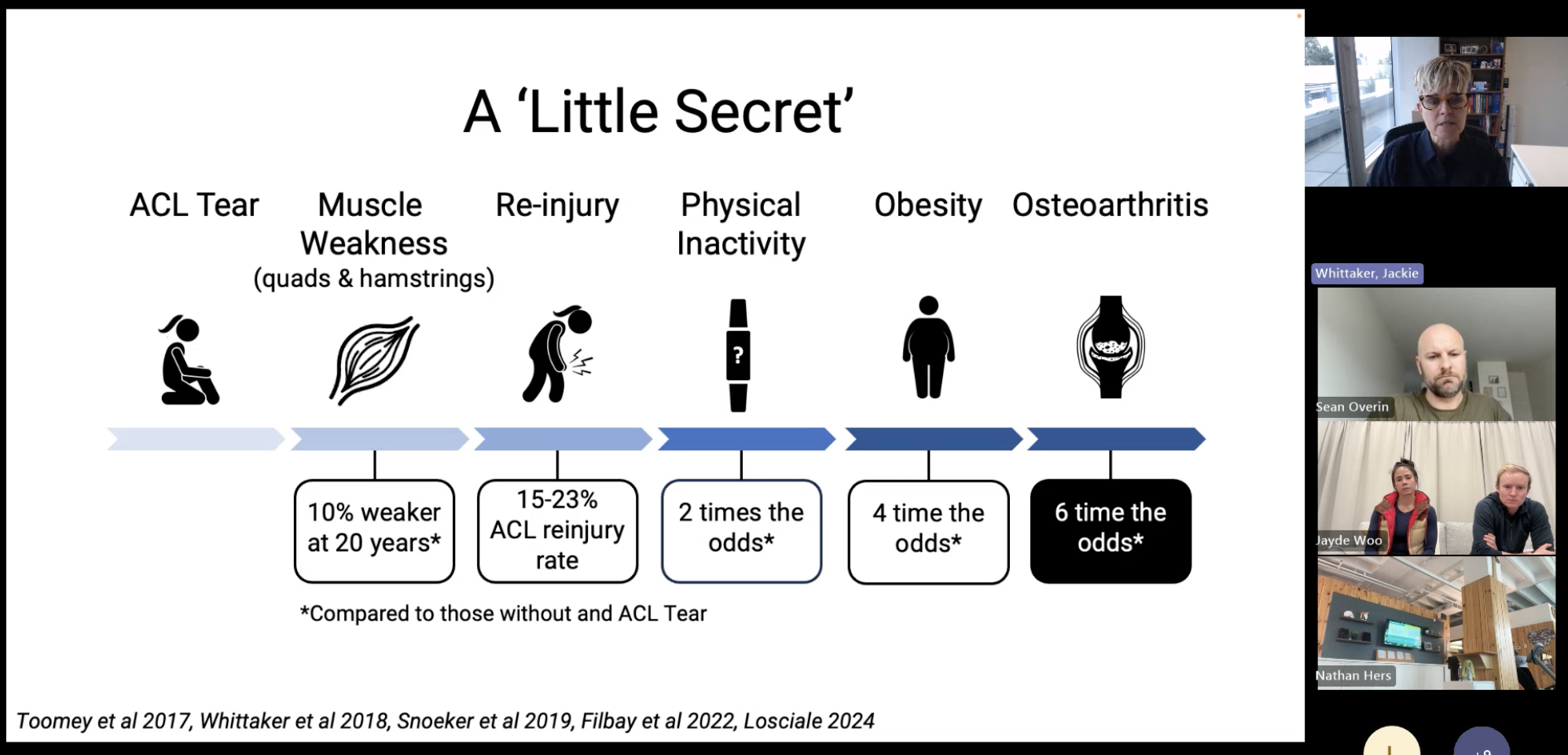

It wasn’t just about cartilage changes, or the sobering fact that

half of young people will develop symptomatic knee OA by their 40s. It was about

systems — how musculoskeletal (MSK) health largely sits outside our public-health infrastructure, and why that matters for prevention, research, and the long-term health of our communities.

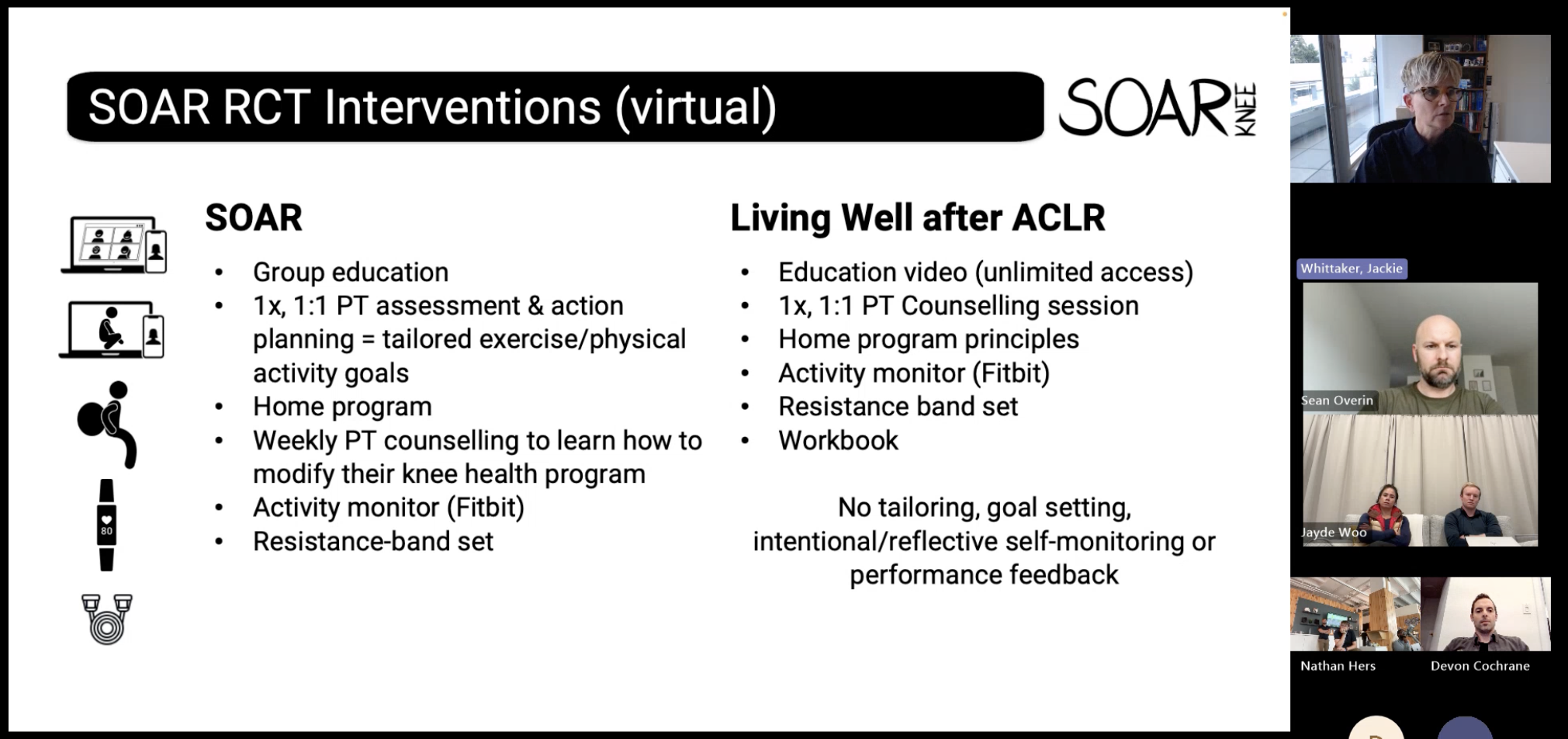

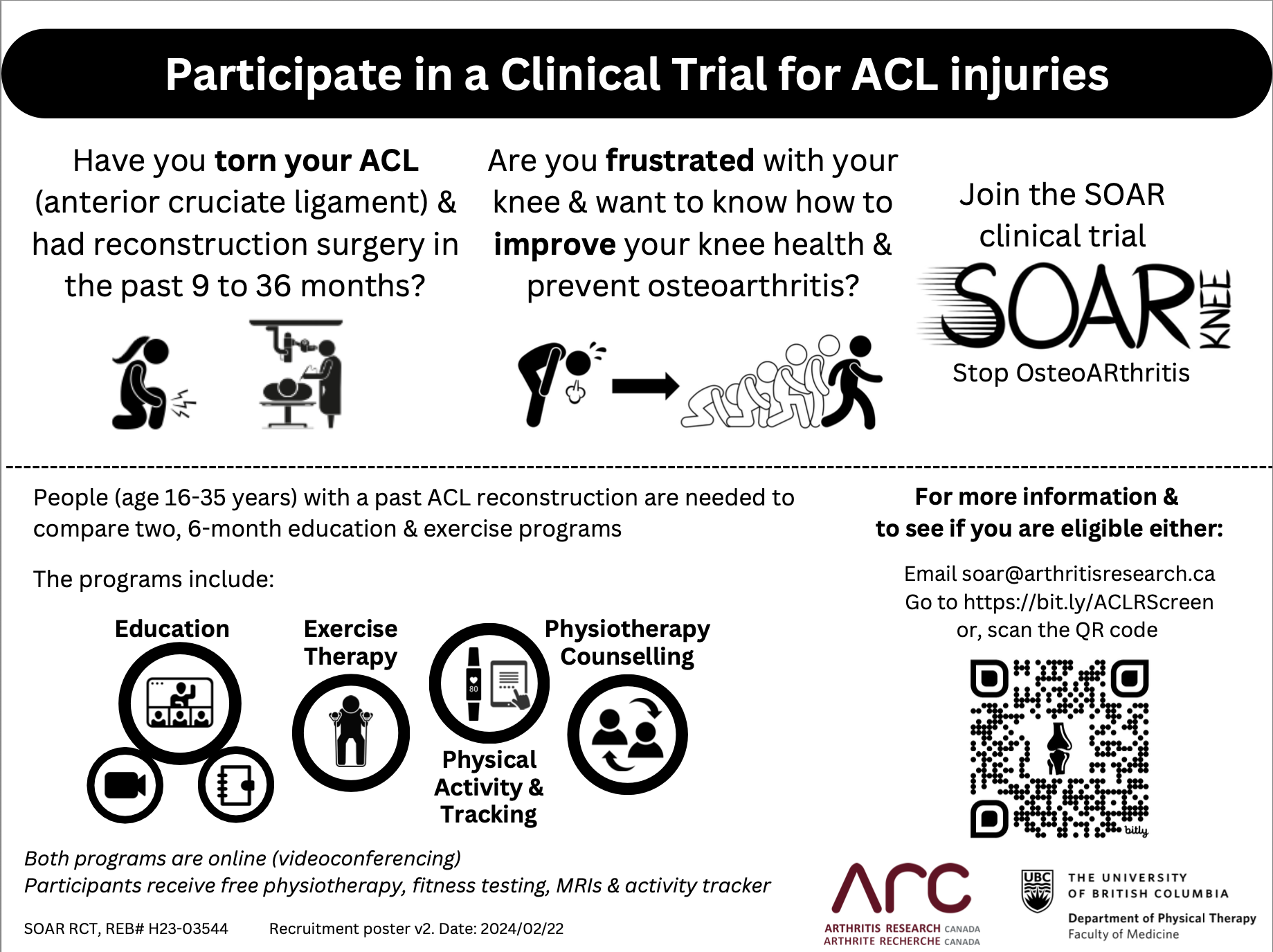

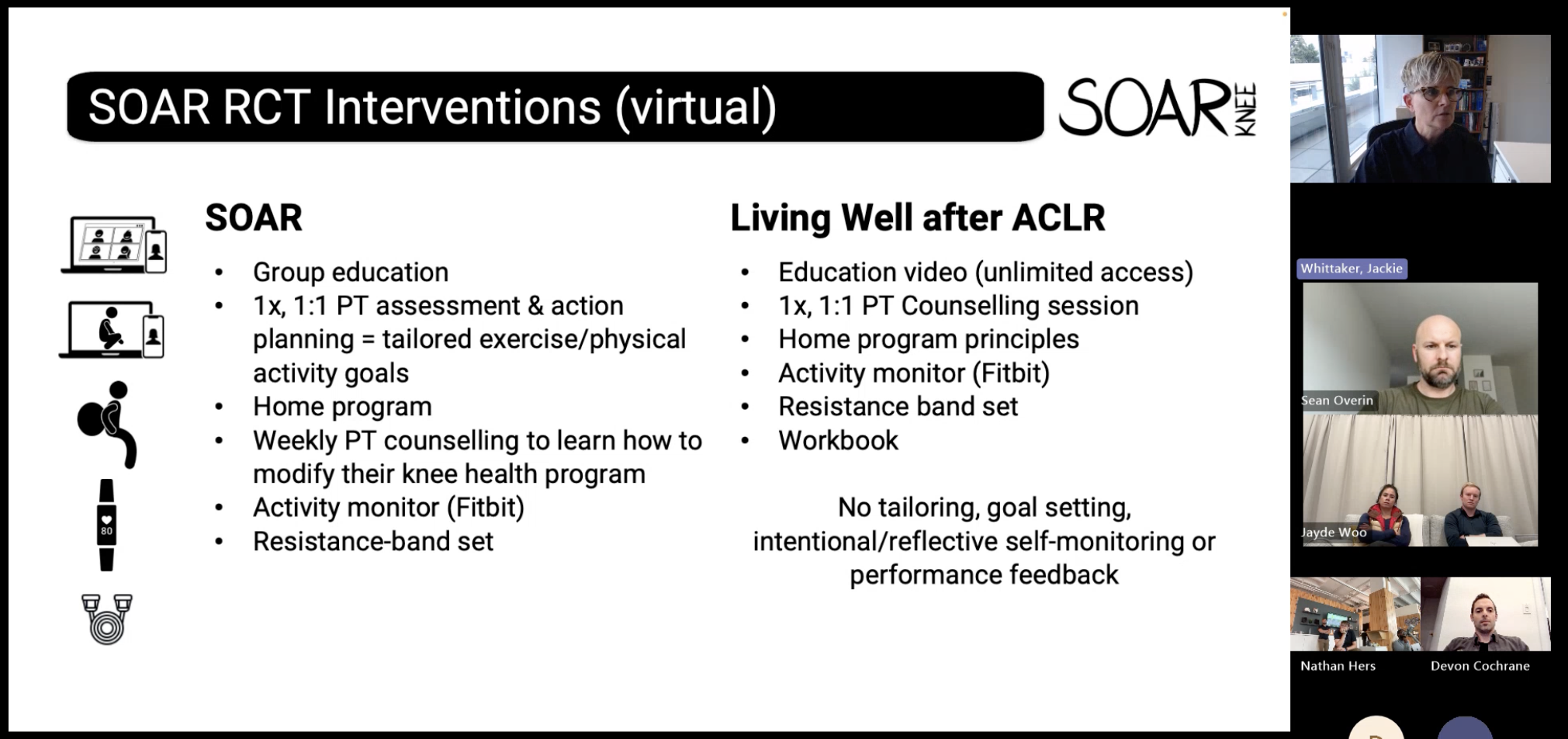

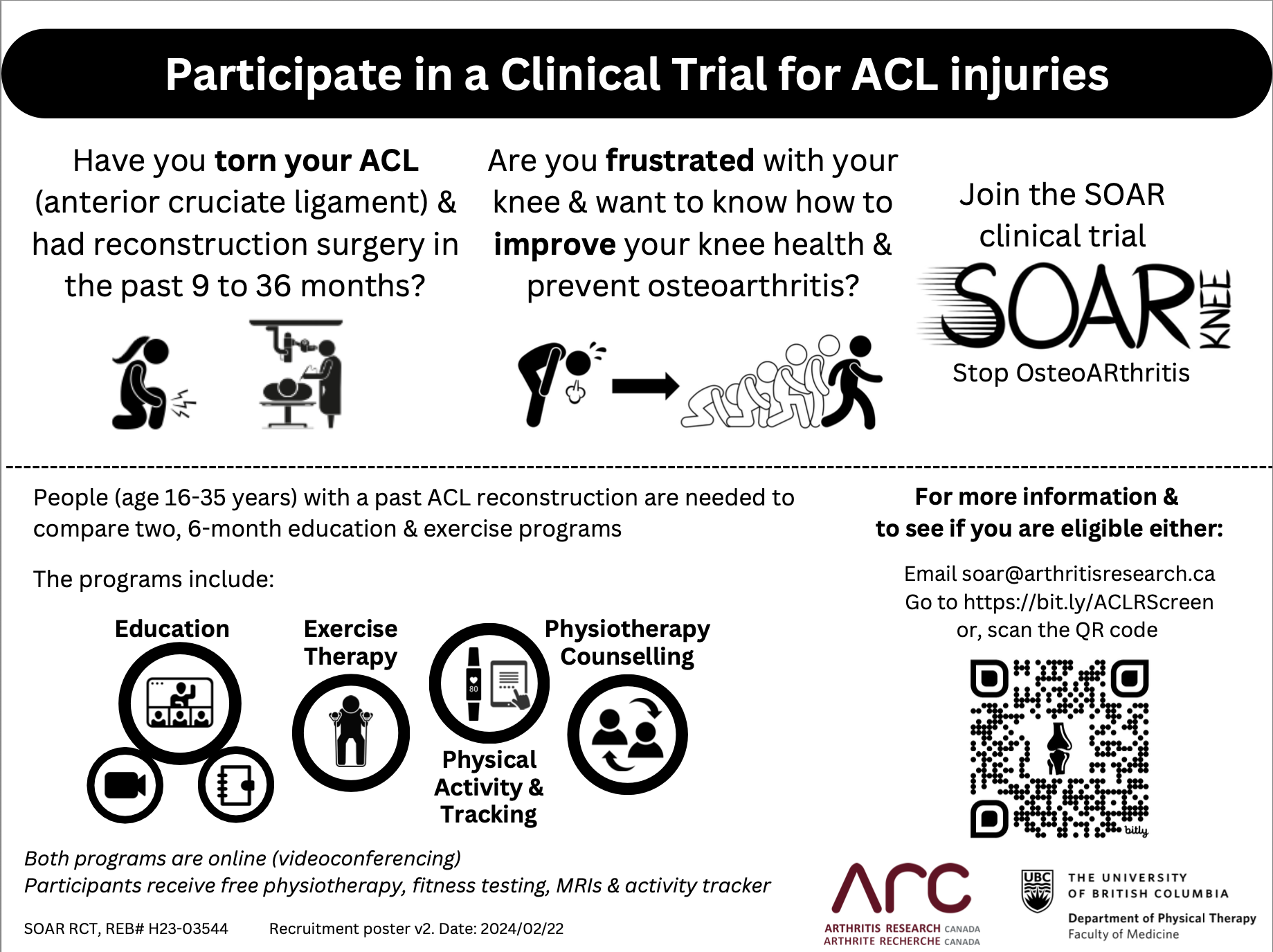

Jackie highlighted her and her teams tireless work on the

SOAR program (Stop OsteoARthritis) and is a strong example of an evidence-based MSK initiative that works on multiple fronts. It’s helps people recover from traumatic knee injuries or surgeries — ACL, ACLR, or otherwise — to rebuild strength, stay active, manage adiposity, and reduce long-term OA and chronic disease risk. The program is

clinically effective, cost-saving, and built to be delivered by community clinicians like us.

Yet, like many interventions that

work, it lives in a

funding no-man’s-land between research and healthcare delivery — supported by data, embraced by clinicians, but largely unsupported by the systems meant to sustain it.

This is starting sound like another example of good research taking 17 years to get into practice. (

ref)

So the question becomes:

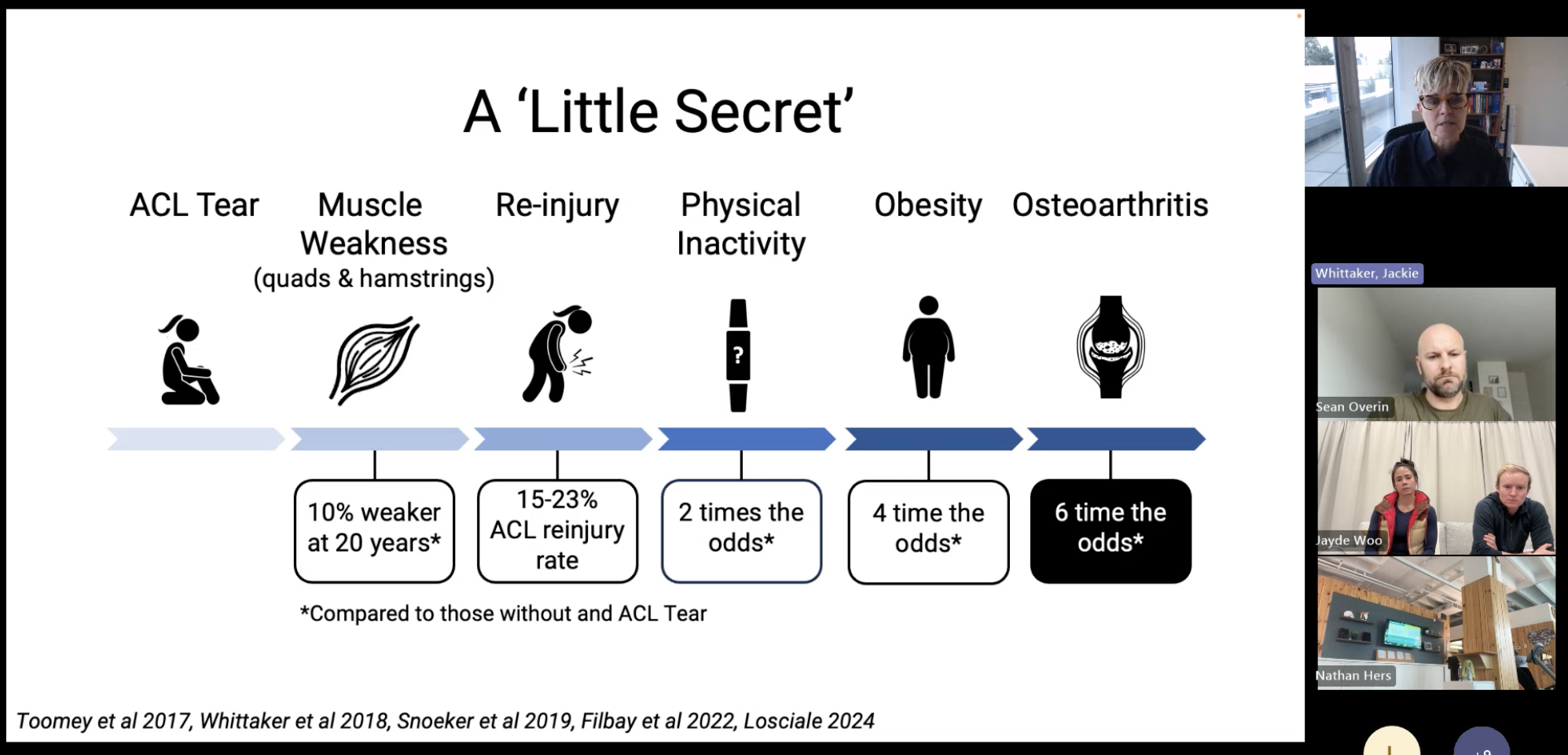

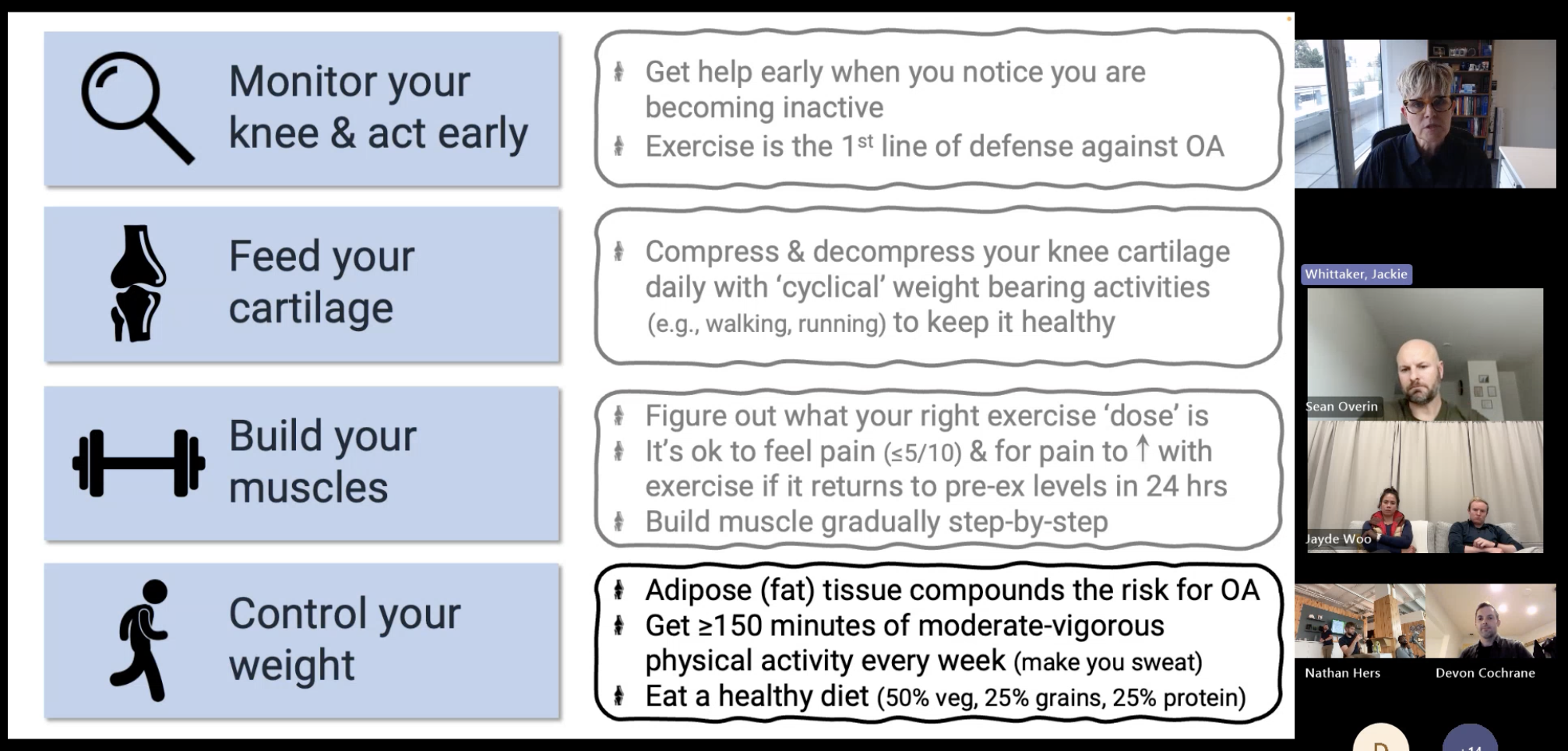

how can we build systems that connect research to proven MSK interventions like SOAR, and link them to public-health structures that fund and sustain care — to prevent downstream health risks and system costs?Great slide from the presentation above: Jackie is getting at how many people believe that if they do their rehab and surgery as prescribed, their knee will recover fully and, to be fair, that’s often what we as healthcare providers imply.

But again, the evidence is clear: knee injuries are

not self-limiting — even with rehab, they often lead to long-term strength loss, re-injury, inactivity, and, for about

50% of people, osteoarthritis within 10–15 years, often by age 40. (

ref). Long term behaviour is needed.

Jackie drew a powerful comparison between Alzheimer’s disease and knee OA.

In Alzheimer’s, patients move through publicly funded systems — from hospital to specialist to research. Clinical trials and care are integrated; funding and data flow under one umbrella. Prevention and treatment are inseparable from research.

For MSK conditions, the picture is reversed.

The majority of care happens in private community clinics, disconnected from health authority systems, policy levers, and research infrastructure. So even when strong evidence emerges — like the SOAR program — there’s no public pathway to scale it.

Clinicians are ready. Researchers have data. Health systems bear the downstream costs.

The connective tissue is missing.

We’re facing a paradox:

We know what works — yet can’t deliver it at scale.

Knee OA is not self-limiting.

Again, roughly 50% of people with a traumatic knee injury will develop osteoarthritis within 10–15 years, often before age 40.

That’s a staggering number, considering the volume of ACL and meniscal injuries seen each year. Persistent quadriceps weakness, re-injury, and inactivity create a cascade that leads to early OA, work loss, and health decline.

Women face even higher risk — with more injuries, lower return-to-sport rates, and higher inactivity as adults.

We have evidence-based strategies that can prevent or delay OA — programs like SOAR show the way — yet our health system isn’t structured to deliver them.

The

OPTIKNEE Consensus Statement (

Whittaker et al., BJSM 2022) pulled together international experts to translate decades of research into actionable recommendations for preventing post-traumatic knee OA.

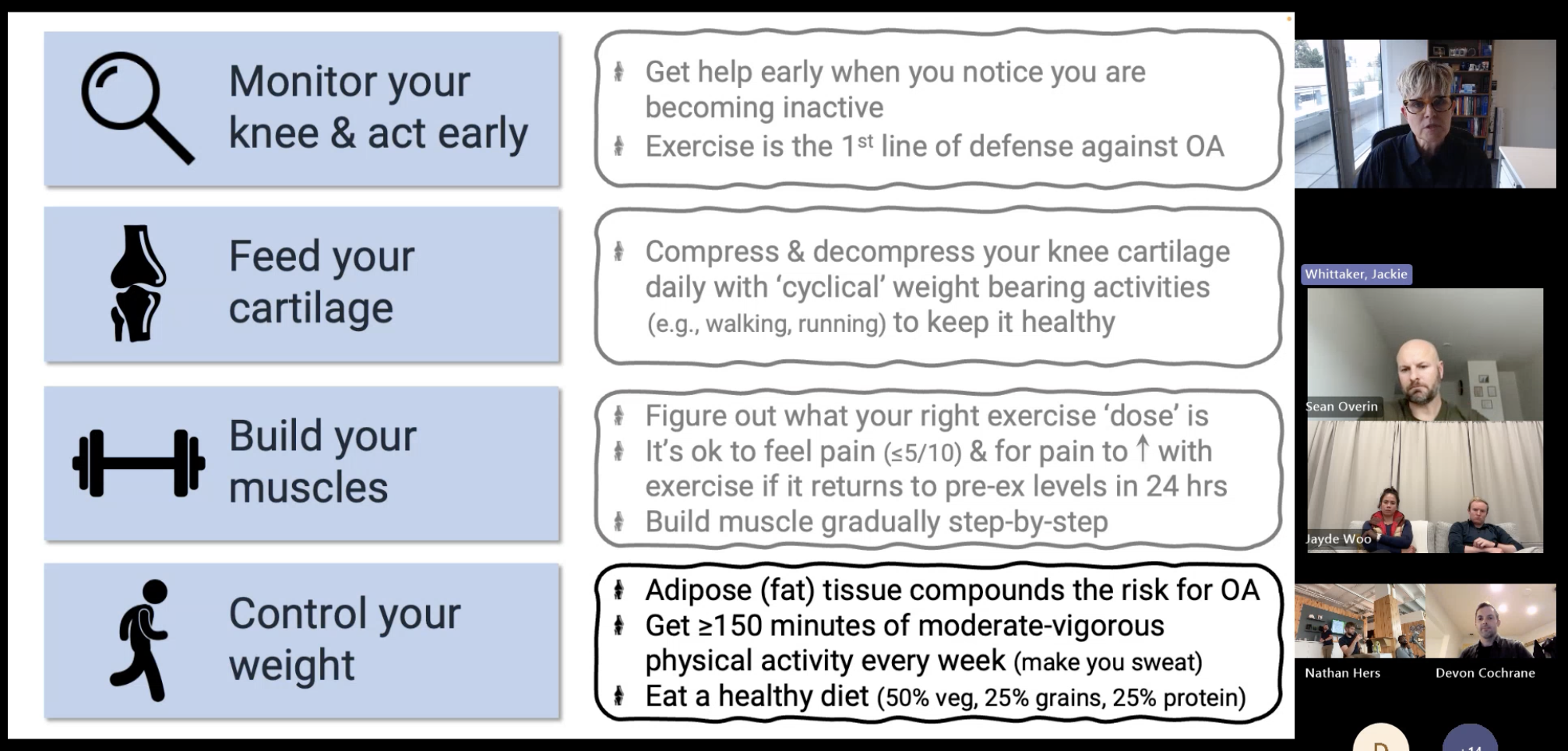

Here are a few that stood out:

🏋️ 1. Restore Strength Early and Maintain It Long TermQuadriceps weakness is one of the strongest predictors of long-term OA.Ongoing strength and neuromuscular training should be a lifelong prescription, not just a phase of rehab.

⚙️ 2. Standardize Rehab After ACL and Meniscal InjuryHigh variability in post-injury care contributes to poor outcomes.OPTIKNEE recommends

criterion-based progression, targeting symmetry in strength, movement, and function before return-to-sport.

🚫 3. Avoid Premature Return to SportRe-injury rates remain high when return is time-based rather than criterion-based.

Each additional injury accelerates OA risk.

🩹 4. Integrate Secondary PreventionRehab shouldn’t end at discharge.

Structured, long-term follow-up — like SOAR’s 12-month program combining education, exercise, and behavior support — is feasible and effective in community settings.

🧩 5. Bridge Research and PracticeThe paper calls for

implementation science approaches — embedding research within real-world clinics, using data feedback loops to refine care, and testing scalable delivery models.

In short, it’s a roadmap for preventing OA before it starts —

but only if we can align the system around it.And that’s the thread that ties everything together.

We already have the evidence — from

SOAR, from

OPTIKNEE, from decades of

MSK research — showing what works.

The gap isn’t knowledge or clinician readiness.

It’s that

our systems aren’t structured to deliver or sustain what we know works.So the question becomes:

how do we build the connective tissue — between research, clinicians, and policy — so evidence-based programs like SOAR become standard, not exceptional?

Maybe it starts with a new kind of

partnership model — one that connects researchers, public health, and community care.

Picture this:- Health authorities fund pilot implementations of evidence-based OA-prevention programs in private clinics.

- Researchers embed within those clinics to collect outcomes, refine delivery, and publish real-world data.

- Funding is tied to preventive outcomes — not just service units.

- Clinics become innovation labs.

- Researchers gain community access.

- Health systems reduce long-term burden.

- Patients get earlier, evidence-based care.

It’s a different way to think about

bundled or innovation-based funding — one that rewards prevention, collaboration, and learning in real time.

We already know what works.

We just haven’t built the system to deliver it.

And I’ll be the first to say —

I don’t have all the answers here.I’m a clinician, not a policy maker or researcher. But maybe someone out there does.

If you’re working in this space — implementation, health economics, or public system design — I’d love to learn from you.

📄 Read the OPTIKNEE Consensus Statement:

BJSM 2022This paper pulled together experts from around the world to turn decades of research on post-traumatic knee OA into clear, practical recommendations.It’s basically a playbook for how we can prevent OA before it starts — and make rehab after injury actually count long term.

🧩 Learn more about SOAR:

SOAR RCTSOAR (Stop OsteoARthritis) is a program that helps people recovering from knee injuries rebuild strength, stay active, and lower their long-term OA risk.The RCT showed it works — it’s effective, cost-saving, and ready to be delivered by community clinicians like us.

If you work with post-traumatic knee injuries, these are must-reads.

This conversation exposed a deeper truth about MSK health: it’s still waiting for its public-system moment.

Imagine if every ACL reconstruction automatically triggered a referral to a community-based SOAR program — funded, tracked, and linked to outcomes data shared with health authorities and research teams.

Maybe that’s a bridge Jackie was pointing toward: a system where research, patients, and care aren’t separate silos, but parts of one continuous learning loop.

It’s not impossible — it needs architecture, partnership, and will.

Let’s start imagining what that could look like.