Do our forms and scales give people a voice — or shut them down?

Pain scales and long intake forms can flatten a layered human story into a number. No one enjoys filling them out—and when patients don’t see their words reflected back in the session, they stop expecting to be heard. As Carolyn shared, “If the first thing I do is fill out pages no one reads, I already feel unseen.”

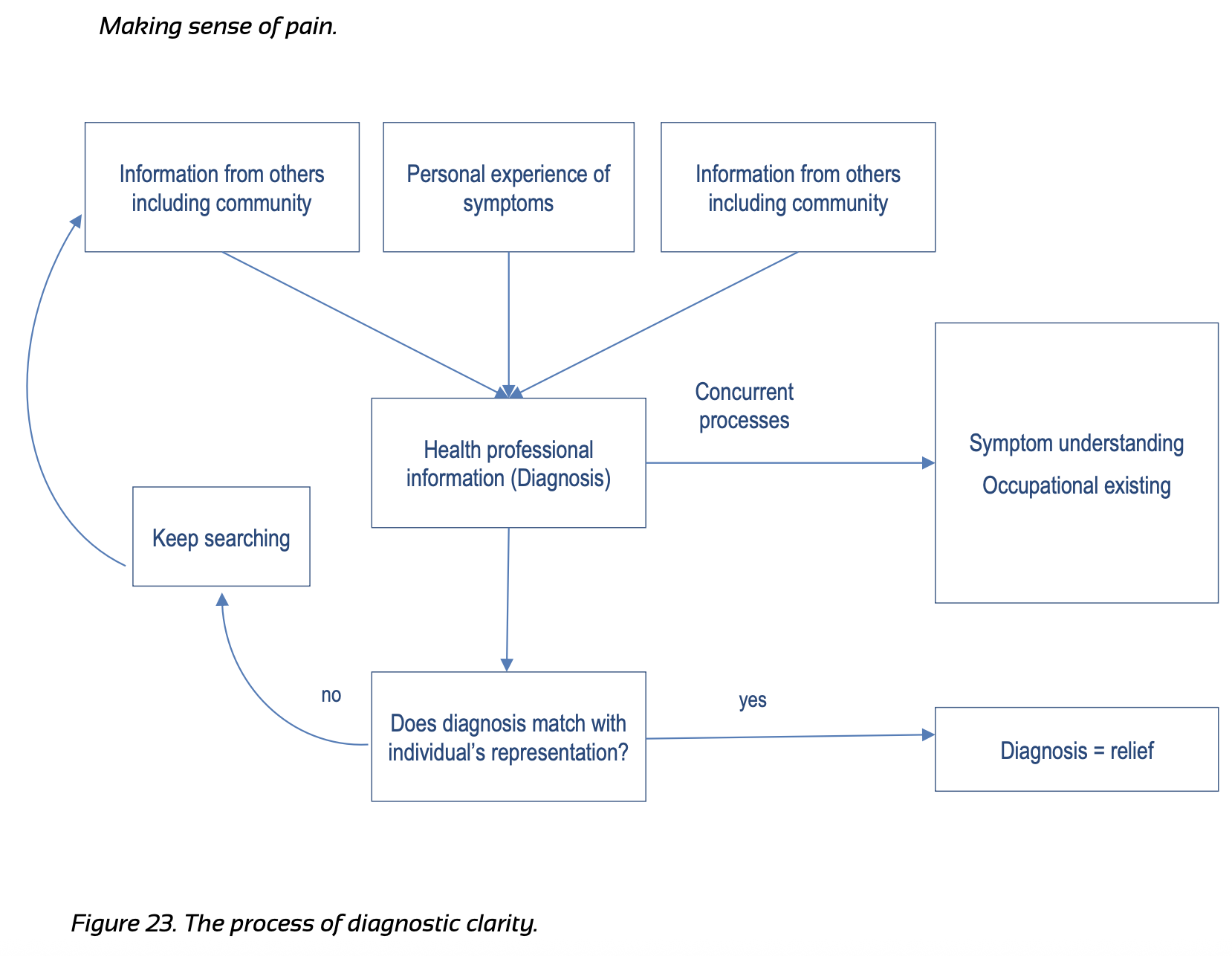

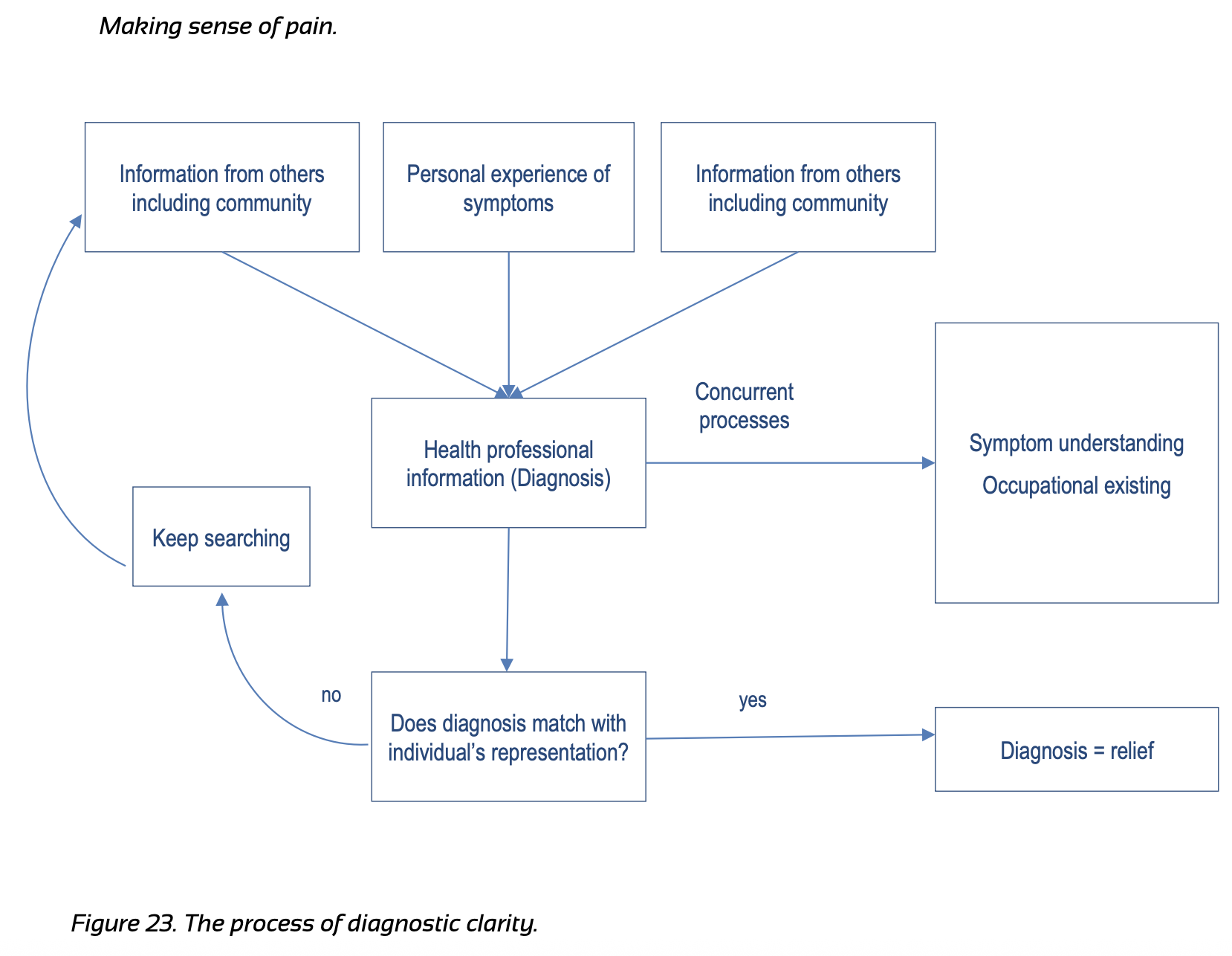

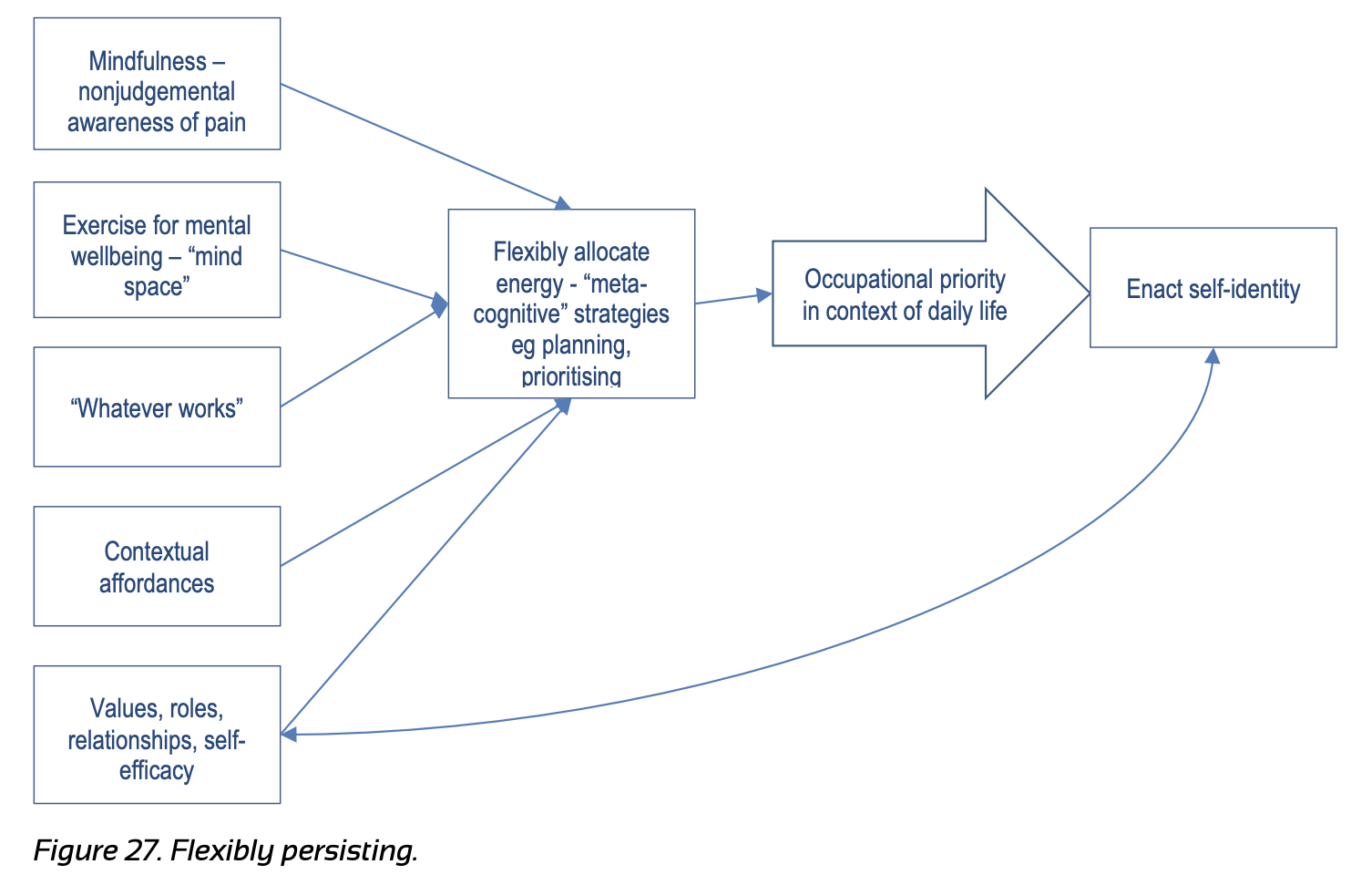

Research by Bronnie Lennox-Thompson reminds us that people who live well with chronic pain cultivate self-coherence—a sense of wholeness—by shifting from patient to person. The intake form is often the first invitation into that shift, a chance to see someone’s full experience, not just their symptoms.

Yet too often, our forms are designed to capture what’s wrong, not what matters—collecting pain sites, severity scores, and co-morbidities, while missing the values, hopes, and context that bring meaning to care.

🧭 Reframe the Intake as Connection

Small clinical redesigns that matter:

Start with purpose questions:

These orient you both toward values and function, not just pain

“Who or what matters most right now?”

These answers anchor the care plan to roles, not body regions.

“What’s your go-to strategy?”

Now the patient is co-authoring their regulation plan.

🩺 How to use the Form:

Pain scales and long intake forms can flatten a layered human story into a number. No one enjoys filling them out—and when patients don’t see their words reflected back in the session, they stop expecting to be heard. As Carolyn shared, “If the first thing I do is fill out pages no one reads, I already feel unseen.”

Research by Bronnie Lennox-Thompson reminds us that people who live well with chronic pain cultivate self-coherence—a sense of wholeness—by shifting from patient to person. The intake form is often the first invitation into that shift, a chance to see someone’s full experience, not just their symptoms.

Yet too often, our forms are designed to capture what’s wrong, not what matters—collecting pain sites, severity scores, and co-morbidities, while missing the values, hopes, and context that bring meaning to care.

🧭 Reframe the Intake as Connection

Small clinical redesigns that matter:

Start with purpose questions:

- “What would make today a win for you?”

- “What are you hoping to get back to?”

- “What’s one activity you’d love to do more often—even if pain stays?”

These orient you both toward values and function, not just pain

- Pair pain ratings with function and consistency:

- Add an identity panel:

“Who or what matters most right now?”

These answers anchor the care plan to roles, not body regions.

- Capture the flare story:

“What’s your go-to strategy?”

Now the patient is co-authoring their regulation plan.

🩺 How to use the Form:

- Actually read the form! Many reluctantly spend time filling it out. Acknowledge it and thank them for doing so. Incorporate it into your conversation.

- Mirror back a sentence they wrote. “You said you want to walk your dog 20 minutes. Tell me more about this.”

- Document visibly: Start your note with their words — Goal: play with my kids without fear.