Chen et al., Pain (2018): A 5-year back pain crystal ball.

Unfortunately, the narrative that “it’ll just get better” doesn’t hold up.

This study followed people for 5 years and found 4 clear pain trajectories—plus some early flags for who’s likely to struggle:

Unfortunately, the narrative that “it’ll just get better” doesn’t hold up.

This study followed people for 5 years and found 4 clear pain trajectories—plus some early flags for who’s likely to struggle:

🔍 The 4 Pain Paths

- No or Occasional Pain – These folks bounce back fast. 🙌

- Persistent Mild Pain – Some nagging, but manageable.

- Fluctuating Pain – Up, down, up again—like a yo-yo 🎢

- Persistent Severe Pain – The tough one. Pain sticks around. 😣

Spoiler: 25% landed in the persistent severe group—but that’s the crew we’re most worried about.

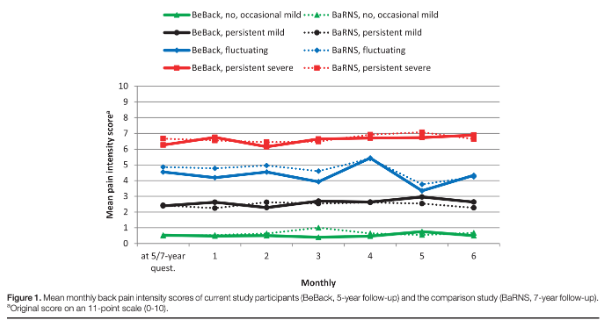

This figure shows the four long-term pain trajectories identified in the Chen et al. (2018) study, comparing two different cohorts: BeBack (5-year follow-up) and BaRNS (7-year follow-up).Each line represents mean monthly back pain intensity scores over time (0–10 scale):

🧠 Key insight: These patterns are remarkably stable over years—reinforcing the idea that early identification of trajectory (and intervening accordingly) could change someone’s long-term experience of back pain.

- Green (No or Occasional Mild Pain): Very low pain throughout—consistently around 0–1.

- Black (Persistent Mild Pain): Steady low-level pain (~2–3), showing little fluctuation.

- Blue (Fluctuating Pain): Pain levels bounce around (4–5), with noticeable month-to-month shifts.

- Red (Persistent Severe Pain): Consistently high pain (~6–7) across the entire follow-up period.

🧠 Key insight: These patterns are remarkably stable over years—reinforcing the idea that early identification of trajectory (and intervening accordingly) could change someone’s long-term experience of back pain.

🚨 Who’s at Risk for a Rough Ride?

Some signs scream “this could get sticky”—and they show up early.

🔬 Early life adversity & genetics – Set the stage for a sensitive system

😰 Chronic stress – Keeps the volume knob turned up

🧠 Mental health conditions – Depression, anxiety, trauma = higher risk

🔥 Higher baseline pain – The fire’s already burning

😟 Unhelpful beliefs – “I’ll never get better,” “My back is damaged”

🛋️ Passive coping – Resting, guarding, avoiding

📉 Lower socioeconomic status – Social disadvantage makes everything harder

👉 Spot these early, and we’ve got a better shot at changing the story.

🧠 Translation: People weren’t doomed by their back—they were thrown off course by fear, beliefs, and life stress. This really aligns with what patients expect from their therapist — a plan that addresses biology and psychology.