This week, we’re revisiting something that comes up all the time in clinical practice—movement as medicine.

We say it constantly. It’s a foundation of rehab, health promotion, and public messaging. But what if movement isn’t always helpful? Or at least, not in the ways we assume?

A new study out of Copenhagen just added more weight to an idea that’s been lurking in the literature for a while: the physical activity paradox.

This paradox is something I’ve wrestled with personally—especially when working with patients who are physically active all day at work but still in pain. We tell people that movement is good. And it is. But if you’ve ever had a patient who works construction, cares for patients in long-term care, or stocks shelves at a grocery store—you know it’s not that simple.

Let’s dig in.

This new study from

Johansson et al. (2025) used data from the

Copenhagen City Heart Study—a large, well-established cohort of Danish adults—and examined how two types of movement relate to persistent musculoskeletal (MSK) pain:

- Leisure-Time Physical Activity (LTPA)—like exercise, sports, hiking

- Occupational Physical Activity (OPA)—like lifting, walking, standing, and bending during work

Here’s what they found:

- People with high LTPA had 42–62% lower odds of persistent MSK pain

- People with high OPA had 3x higher odds of persistent MSK pain

- And here’s the kicker: even if someone was highly active in their leisure time, it didn’t cancel out the risk from a physically demanding job

That finding hits. Because I’ve seen this frustration play out again and again in clinic.

People come in, exhausted and sore after long shifts of heavy work, and then feel like they’re supposed to do even more on top of that. They’re told, “movement is medicine,” but the movement they’re doing all day is grinding them down. Now they feel like they’re failing because they’re in pain, even though they’re active.

I wish it were as simple as telling people to just move more. But this paper reinforces what we already intuitively know: the type, intensity, duration, and context of movement matters.

Not all physical activity confers the same benefits.

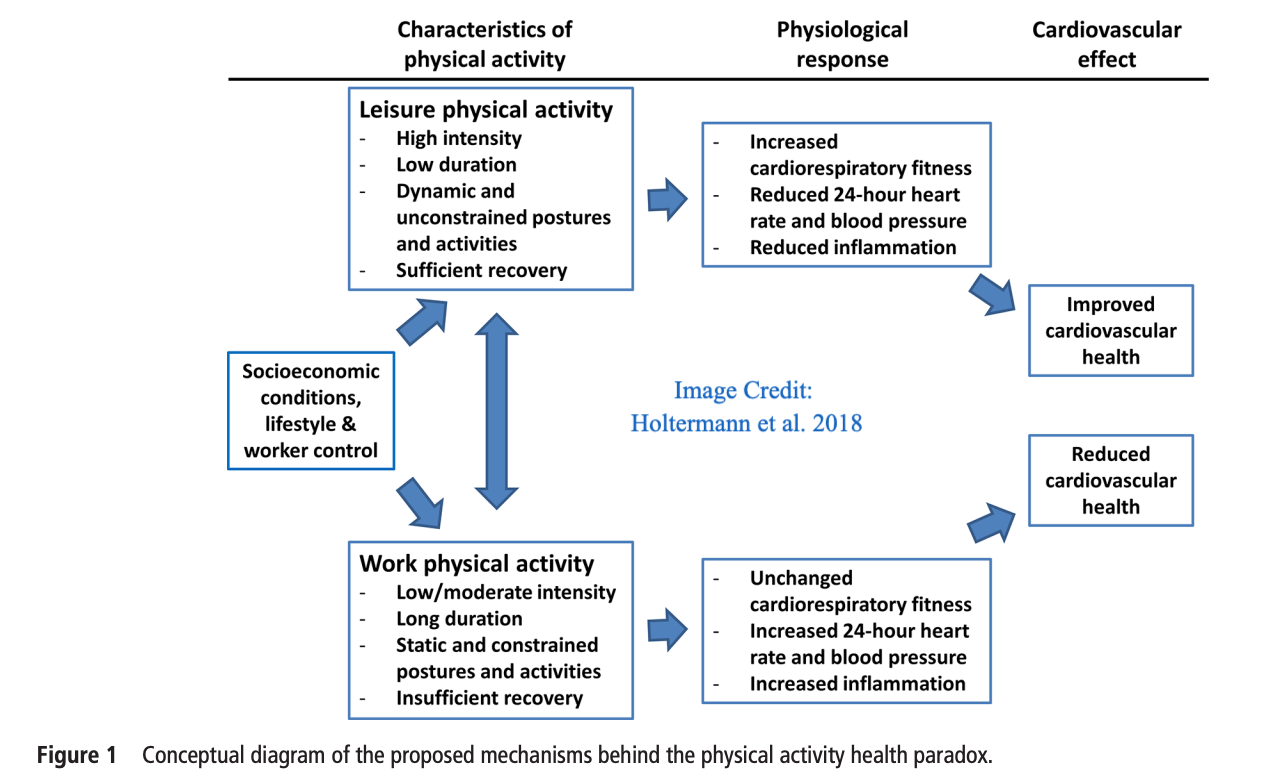

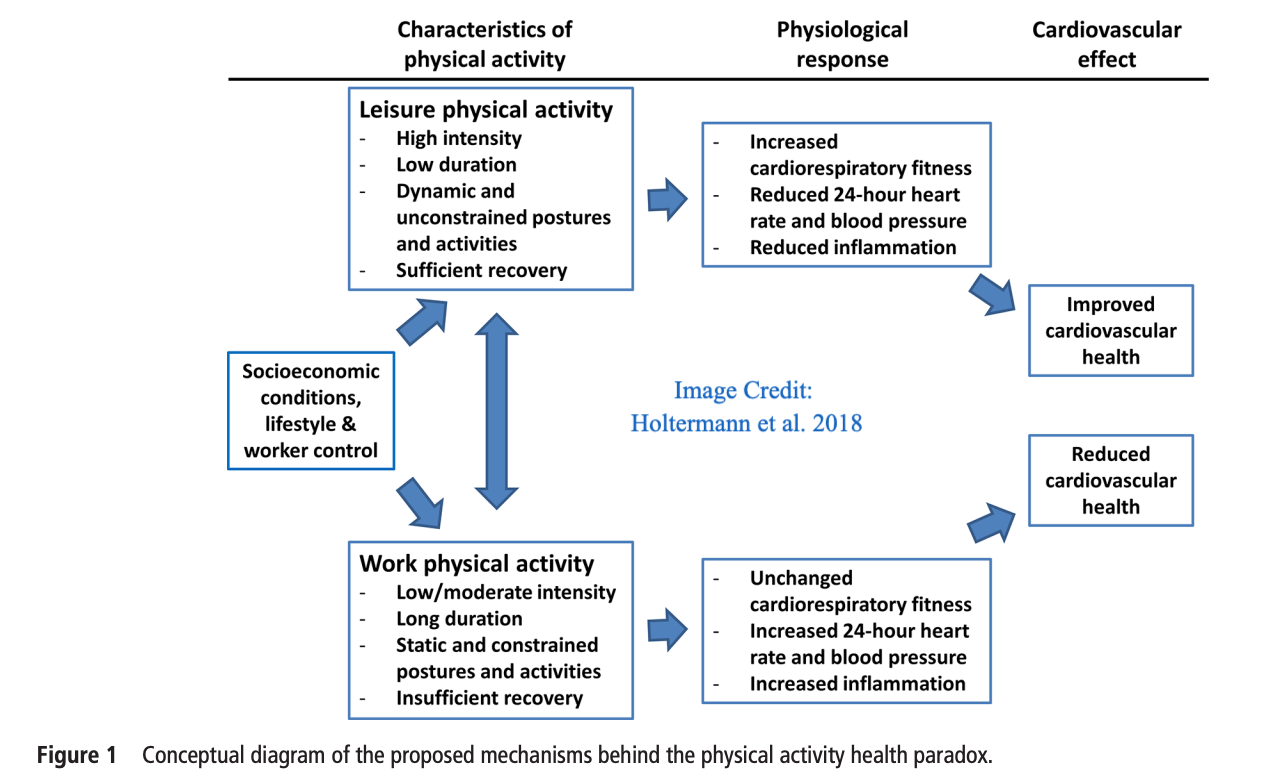

Here’s how I’ve come to understand the difference:

- LTPA tends to be: voluntary, self-paced, higher-intensity, and includes rest and recovery

- OPA tends to be: repetitive, prolonged, non-volitional, and often tied to stress, low control, and high demand

That matters.

Exercise loads the system with intention, typically in short bursts, and includes time to rebuild. OPA often loads the system relentlessly at times, without regard for pacing or pause.

So it’s not just about energy expenditure or steps per day. It’s about intention, the perception of that load, the environment it happens in, and whether recovery is built in.

This paper also found that people in high-OPA jobs had up to 78% more pain sites than their sedentary counterparts. That’s not a little discomfort—that’s widespread, persistent MSK pain.

We need to be thoughtful about how we talk about movement. Especially with patients who are already giving everything they have—physically and emotionally—at work.

Here’s something to try...

“How does your body feel after a day at work compared to after a workout?”

This simple question opens up so much.

You’ll hear things like:

→ “Work just drains me.”

→ “I’m tense and sore by the end of my shift.”

→ “Exercise actually helps. Work wrecks me.”

It helps me quickly understand whether someone’s physical activity is contributing to resilience—or compounding fatigue.

From there, we can shift toward strategies that support load management, recovery, and autonomy:

- Pacing strategies during the workday

- Emphasizing rest as a therapeutic intervention

- Using strength training to improve tissue capacity (without just adding more fatigue which is common concern amongst these folks)

- Educating on postural variety and micro-breaks

- Exploring workplace ergonomics and psychosocial stressors

This is the stuff that often makes the biggest difference—but it starts with asking the right questions.

📘 Six reasons why occupational physical activity doesn’t confer the same health benefits as leisure-time activity—

Holtermann et al., BJSM (2018)This short commentary has become one of my go-to resources when explaining the physical activity paradox to both patients and peers.

It unpacks the key reasons OPA doesn’t deliver the same cardiovascular or MSK benefits as LTPA—including lack of intensity variation, insufficient recovery, and limited autonomy. It also touches on

psychosocial stress, which is often overlooked when we talk about physical activity.

If you’re teaching, mentoring, or creating content—this is a fantastic explainer.

“For some, you can’t weekend-warrior your way out of occupational strain.”

That line comes back to me often—and it gets to the heart of this paradox. We can’t assume all movement is helpful, or that more is always better. Especially for those already spending their days on their feet, lifting, bending, or rushing from task to task.

Reframing movement through the lens of recovery and resilience is essential.

Instead of simply suggesting exercise which maybe interpreted as just more movement by our patient's, we need to help them understand that rehab and building capacity isn’t about piling on more reps or kilometers—it’s about introducing variability, endogenous pain relief, agency, prioritizing recovery, and building strength with intention.

When we get that balance right, we don’t just reduce pain—we enhance performance and help people sustain their bodies over time.

Recovery is resilience. And for patients with high occupational loads, what they do outside of the job site might be the most powerful place to intervene we can help them intervene.

Stay nerdy,