Jan 12 • Sean Overin

What the Science Actually Says About Habits

Empty space, drag to resize

A quick year-in-reflection moment: one of my goals last year was to find a regular writing outlet… and I actually did. This newsletter became that space. I genuinely enjoy writing—whether people are reading it or not—but I really appreciate when you reply because (a) it tells me you’re enjoying the content, (b) I’m learning from you, and (c) it keeps reminding me what a great community of rehab pros is out there.

Another goal was to step back a bit from social media. That one was successful and refreshing. I don’t tend to think about balance...I think about momentum and energy that adds to my flywheel. Social media tends to take energy away. Writing adds to it. There’s a tradeoff there. And wow… social media feels noisy these days, right? Or maybe I’m just getting older. Either way, I’m not missing it much.

AMP was a year of building. We took a lot of ideas out of our heads and turned them into courses. There’s still a bit more to come, but I’m proud of what we shipped. This year, we’re keeping it simple: more writing, more teaching, and more good stuff for our community of rehab pros.

Empty space, drag to resize

That reflection ties perfectly into what this week newsletter is about: habit formation.

This newsletter didn’t become “a habit” because I wrote for 21 days straight. It became a habit because it fit into my week, added energy instead of draining it, and was easy enough to return to, even after breaks (like this one).

Same thing with stepping back from social media. That wasn’t about willpower. It was about energy, environment, and alignment. Which is exactly what we’re asking our clients to navigate every day.

So let’s talk about habits and how habits form in real life.

We’ve all heard it: “It takes 21 days to form a habit.”

It sounds clean. Reassuring. Easy to remember.It’s also not supported by the data...what a surprise right?

So where did 21 days actually come from?

The idea traces back to the 1960s, when a plastic surgeon named Maxwell Maltz noticed something interesting in his patients: after surgery, it often took them about three weeks to psychologically adjust to their new appearance. He also observed similar timelines when people adapted to limb loss or other major changes.

That observation, about adjusting to change versus building habits, slowly morphed into a catchy rule of thumb. Over time, nuance got lost, the number stuck, and “21 days” became habit folklore.

It sounds clean. Reassuring. Easy to remember.It’s also not supported by the data...what a surprise right?

So where did 21 days actually come from?

The idea traces back to the 1960s, when a plastic surgeon named Maxwell Maltz noticed something interesting in his patients: after surgery, it often took them about three weeks to psychologically adjust to their new appearance. He also observed similar timelines when people adapted to limb loss or other major changes.

That observation, about adjusting to change versus building habits, slowly morphed into a catchy rule of thumb. Over time, nuance got lost, the number stuck, and “21 days” became habit folklore.

“Interventions aiming to create habits may need to provide continued support to help individuals perform a behaviour for long enough for it to be subsequently enacted with a high level of automaticity.”

- Lally et al 2009

Fast forward to modern research...

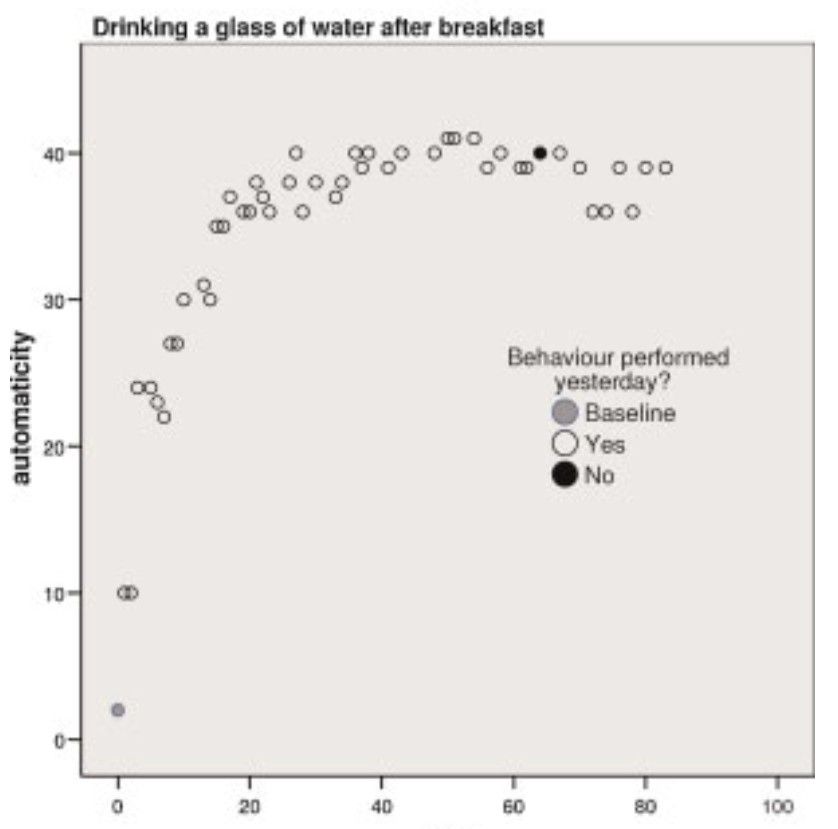

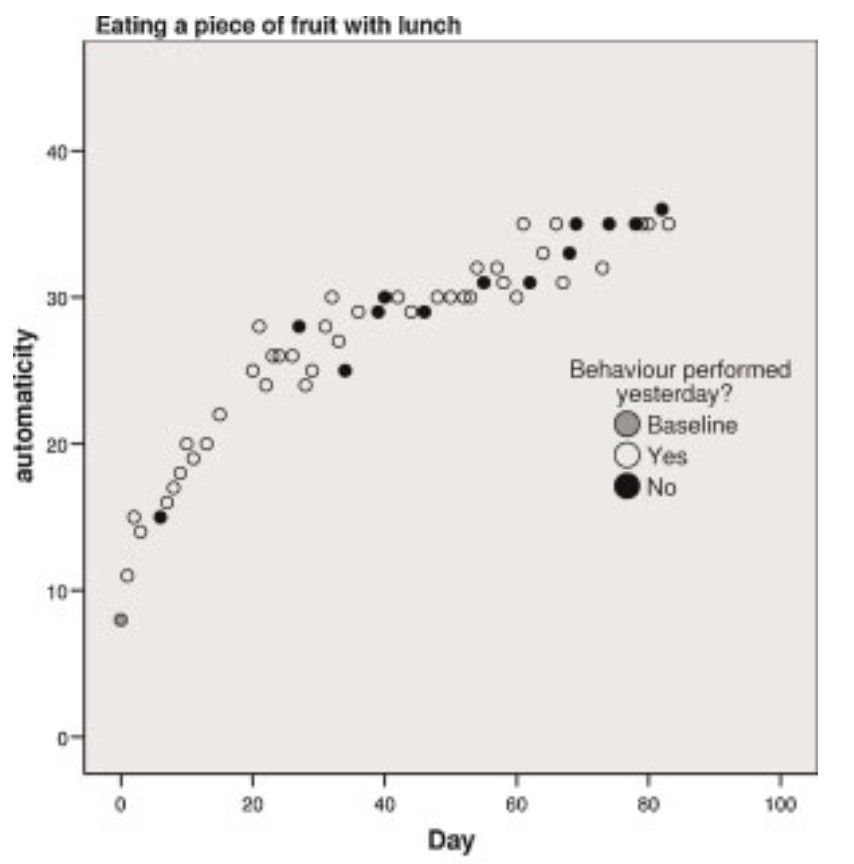

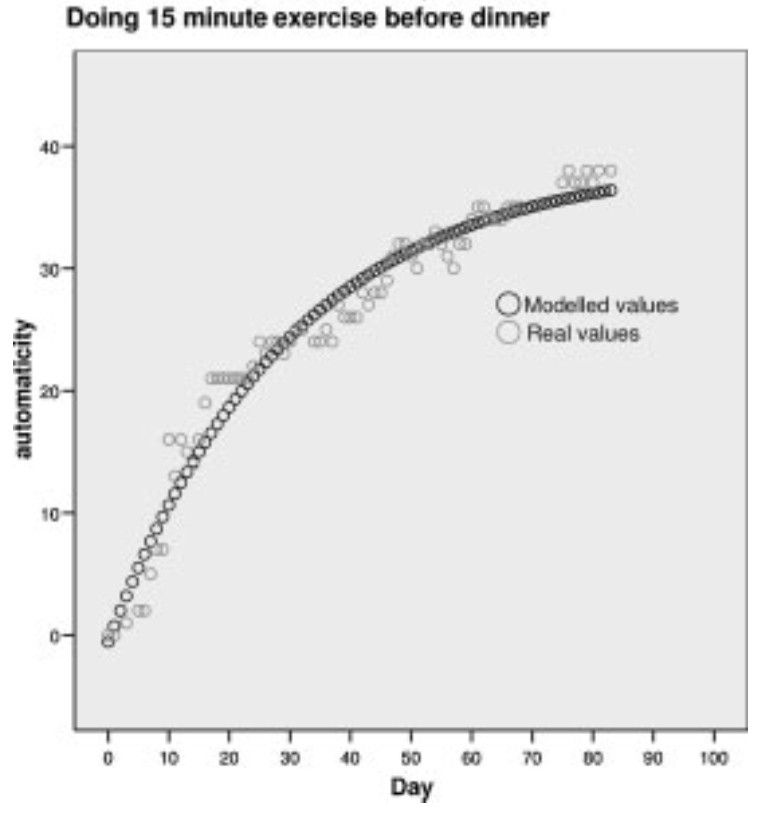

One of the most cited real-world habit studies followed people for 12 weeks, asking them to repeat one simple behaviour in the same context every day (e.g., after breakfast) and track how automatic it felt over time.

What they found wasn’t a straight line, but a curve: fast gains early, then slower progress as habits gradually plateau.

In fact, the average time to reach near-maximum automaticity was 66 days, with a huge range from 18 to over 250 days.

- That “stall” our clients feel after a few weeks?

- That’s normal human behaviour and learning in play

And if we don’t explain that part, people may quit when things are actually working.

What’s often missed is that the type of behaviour matters.

In the study:

- Drinking behaviours (e.g., water after breakfast) tended to reach automaticity faster

- Eating behaviours were similar, but slightly more variable

- Exercise behaviours took the longest on average, often 1.5× longer to feel automatic—even when people were motivated and trying consistently

That makes intuitive sense. Exercise is more complex:

more steps, more effort, more friction, more chances for life to get in the way.

So when a client says, “I’m good at drinking water, but I can’t stick to my exercises,” that’s not a motivation, discipline, willpower problem, it’s a behaviour-complexity problem.

If our rehab plans assume quick lock-in for complex behaviours, we’re setting clients up to feel like they’re “bad at habits,” when really they’re just experiencing normal ebbs and flows of learning.

“Given that exercising can be considered more complex than eating or drinking, this supports the proposal that complexity of the behaviour impacts the development of automaticity.”

- Lally et al 2009

What we’re seeing here

These graphs show how simple vs more complex behaviours turn into habits at different speeds.

The simpler behaviours, like eating fruit with lunch or drinking water after breakfast, become automatic fairly quickly. The curve rises fast early on, then levels off. There are fewer steps, less effort, and a clear daily cue, so the behaviour settles in sooner.

Exercise tells a different story. Doing 15 minutes before dinner still follows the same general pattern, but the curve is slower and longer. It takes more time and more repetitions before it starts to feel “second nature.”

For rehab, this matters. The more moving parts a behaviour has, the longer it takes to feel automatic, even if someone is motivated.

Which is why starting small and anchoring behaviours to clear cues or context can make longer-term rehab plans much easier to stick with.

I will often tell clients that if they are unable to do the plan, make it smaller and keep it paired with the cue.

Try prescribing one cue-based habit.

Ask your client:

“What’s the smallest version of this you could do on a tired Tuesday?”

Then anchor it to a specific moment, not a vague time:

- After brushing teeth → 10 seconds of neck movement

- When the kettle boils → 5 heel raises

- Before the first step out of bed → one slow breath

The research shows habits form when behaviours are repeated in a stable context.

Now, a few clinical examples:

Exercise example

- After I pour my morning coffee, I’ll do one set of sit-to-stands at the counter.

Exposure example

- When I get into my car, I’ll sit for 10 seconds before turning the key.

CBT-style experiment

- When I notice the thought “this will flare me up,” I’ll label it as a thought and take one slow breath before responding.

Small. Intentional. Repeatable.

That’s how habits actually grow.

1) If this way of thinking about habits resonates, I go deeper in a course I built called Habit Formation in Practice. It’s focused on translating habit science into real clinical tools.

We cover:

- Different habit models and when to use which

- How behaviour complexity changes timelines and expectations

- Designing habits that hold up through flare-ups, low motivation, and busy weeks

- Helping clients resume instead of reset when things slip

It’s practical, clinical, and built around the behaviour change challenges we actually see in rehab.

👉 Course link: https://www.amp-healthcare.ca/course/habit-formation

2) If you want to dive into the research behind this approach, this is one of the most cited real-world habit studies:

Lally et al. (2009) followed people building daily habits and showed that automaticity develops gradually, follows a curve (not a straight line), and often takes far longer than the popular “21 days” myth suggests. The key drivers weren’t motivation—but repetition in a stable context and realistic expectations.

3) If you want an accessible complement to the research, Tiny Habits (BJ Fogg) and Atomic Habits (James Clear) are both good reads. Both emphasize starting small, anchoring behaviours to existing cues, and prioritizing consistency over motivation...different styles, same core message: habits stick when they’re easy to repeat and fit real life.

One of the most reassuring findings from the habit research is this:

Missing a few days or reps doesn’t meaningfully derail habit formation. When people return to the behaviour, automaticity keeps climbing.

I think about this a lot when working with clients. People cancel. Life happens. Plans don’t unfold the way we mapped them out. I expect this. Instead of treating it as a problem, it becomes an opportunity to notice what did go well, troubleshoot barriers, and strengthen the working relationship through curiosity rather than guilt.

It shows up here too. I didn’t write every week. I took breaks. And yet, the early reps didn’t disappear. Coming back felt easier because the habit had already started forming.

Empty space, drag to resize

Closing thought

Habit change isn’t about discipline, motivation, or perfect follow-through. It’s about designing behaviours that fit real lives and knowing how to return when things don’t go to plan.

If we can help clients expect interruptions, normalize them, and re-enter the process without shame, we don’t just improve adherence, we build trust. And that, more than any timeline or technique, is what keeps people engaged long enough for real change to happen.

Good luck as you head into 2026.

Keep in touch. Keep up the good work out there.

Stay nerdy,

Sean Overin, PT

Subscribe to our newsletter

Every Friday we cover must read studies, how they fit in practice, give it real world context, provide top resources and one sticky idea.

Thank you!

You have successfully joined our Friday 5 Newsletter subscriber list.